Millennium Approaches and The Kush

At dinner last night, I asked Tanner what he knew about Angels in America and he said:

I know that it is a gay drama—epic gay drama, about AIDS, and angels.

I asked him what he knows about Tony Kushner:

I know that a podcast host I like, Jesse Thorn, refers to him as "The Kush," and he loves him, so now I love him, and I call him "The Kush."

(I'd always thought Tanner coined "The Kush" himself, I'm disappointed. I also wish that my loving a playwright mattered more than a podcast host whose show Tanner doesn't even listen to anymore? But I do love a lot of playwrights, it would be a lot to track.)

Here's what I know about Tony Kushner:

- When I was nineteen, I took a dramaturgy class in college, taught by Oskar Eustis, who was there for the birth of Angels in America and now runs The Public Theater, and one day Oskar walked into class talking on his cell phone and he said to the phone, "Hold on a sec," and turned the phone to us and said, "Kids, say hi to Tony," and we all died.

- Weeks ago on Twitter—I can't find it now—someone said something along the lines of "You have to be very brilliant for Caroline, or Change to be a minor footnote in your career," and this is extremely true. (Though you wanna talk about footnotes, try Slavs!)

- I was a theatre major in college, but it took me a couple years of that to get good at reading plays. For a long time I had trouble tracking characters, hearing their voices, seeing the play as I read. But when I read Angels in America, I looked down to start, and the next thing I remember I looked up, finished, and in between I'd been lost to that world.

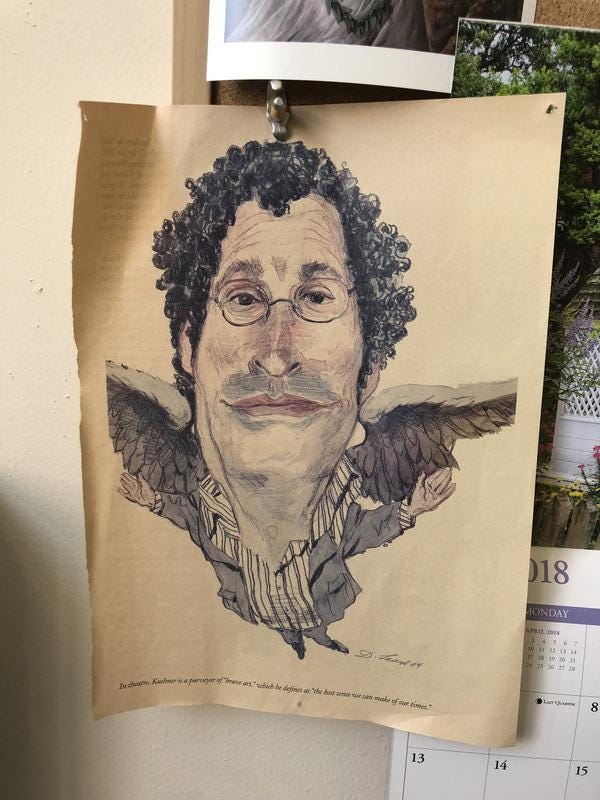

- This picture has hung over my bed, and then desk, for more than a decade:

What else do I know about Tony Kushner? He gains fifty pounds every time he draws close to finishing a project, and then loses it again. I saw him once in the Lincoln Center Starbucks. He seems like he's usually, or often, very sad.

I had never seen Angels in America on stage before. As of writing this, I've only seen half of it. I've read it, and discussed it in class with its first dramaturg, and seen the HBO movie (in which said dramaturg has a cameo in heaven, wearing a fleece zip-up, endearingly out-of-place). But last night was the first time I saw it on stage. When the angel came, I cried because of all the reasons the play gives you to cry, but also because I was finally seeing it.

Afterward, I told Tanner about this note in the script:

The moments of magic ... are to be fully realized, as bits of wonderful theatrical illusion—which means it's OK if the wires show, and maybe it's good they do, but at the magic at the same time should be thoroughly amazing.

They did (the metaphorical wires), and it was (thoroughly amazing).

Sometimes I try to make a list of the times I've cried hardest from a piece of art—books, movies, plays—and sometimes I narrow it down to theatre. There's always Annie Baker's Circle Mirror Transformation (from before she started fucking with the audience, when she was willing to be on our side) which I read as a script when I worked in theatre, and which made me sob then, the kind of cathartic sobbing I usually reserve for the ends of novels, and made me sob again when I saw it as a reading, and again when I saw it performed. There's Adam Bock's A Life, too. I think I cried through the last two thirds of that one, so much that I was shaking at the end on a kind of manic adrenaline rush, because I'd been sobbing and rapt and had never for a second forgotten I was watching a play—the wires showed but it was at the same time thoroughly amazing. It was a preview, and I recognized the director sitting behind me, and so at the end I turned to her, still crying, shaking, and thanked her, and she said, "Are you okay? I was worried—" It was a play about death and sometimes people see those by accident, and end up wrecked all over again from some grief in their life, but for me it had just been the play itself (and, somehow, the set changes). I reassured her, "Yeah, no—it was amazing. Thank you."

The thing that wrecks me in Circle Mirror Transformation, I'm realizing now, is also a moment when the wires show. The play puts a little slip in its story, a fault line fissure in time and the play's world, and every time, it makes me cry because the characters are being given a small narrative gift and, pretty literally, something make-believe is made real.

The thing that made me sob at the end of Hamilton was the staging at the end, Eliza at the center, Lin-Manuel Miranda's choice of that, because what it made me think was, He gave the play to her.

I'm a sucker for the wires, I guess.

I never think of Angels in America as my favorite play, but I take it for granted that it's the best. (I forgot how funny it is, though. It is incredibly funny.) I'd deliberately bought us tickets that spaced the two parts out over two nights—a one-day marathon seemed unbearably intense. But when Millennium Approaches ended last night, when I put my sobbing away and the cast was on their third curtain call, I thought, I don't know how I'm going to wait until tomorrow to see the rest of this! It wasn't a marathon—at least not the slogging way I run. It was past my bedtime and we were just getting started. I don't know. It was magic.

I don't know why I've kept that New Yorker cartoon of Tony Kushner with me all these years. I guess if I'd come across a Sarah Ruhl New Yorker portrait, it'd've been that. But he's always been the pinnacle of something—the best playwright, the best person, most tortured and most troubled. I've met a lot of writers, they're just people, even the brilliant ones. If knowing that writers are people is seeing the wires, he's still somehow something else.