brain tricks

I also decided this week that I'm drawing my own illustrations for the book, assuming this is permitted.

My book is due six weeks from this past Monday. For some reason, six weeks feels like the crunch time, maybe because it's how much time I've ended up with to revise the messy, incomplete first drafts of these chapters into something I feel good about sending to my editor. Today alone I'm restructuring half a chapter, hopefully about 5,000 words, so I'm going to save my lyrical brainjuice for that and instead share with you some things that have been proving helpful as I embark now upon a project entirely to big for my brain to hold at once. Some of this is writing-specific, but plenty of it isn't.

The most helpful thing I've ever learned about writing isn't about writing at all, it's the concept of working memory, which I probably misunderstand, having learned it in the context of teaching writing (and sort of from the classic productivity bible Getting Things Done) and not cognitive science or psychology, but I think of it as what your conscious mind can hold at once. Becoming better at writing—or better at anything—is about making parts of what you're doing automatic so that your working memory isn't busy with things like how to hold a pencil or which squiggle on the staff means "A" and then what's the right key or fingering, but instead you're freed up to think about musicality or your ideas. And so much of teaching writing becomes teaching tricks for taking things out of working memory still to free up that space: not worrying about spelling while you're drafting, or keeping a list of things you want to do in revision so you don't have to remember. I say those are things I teach, but they're things I do, too. Sure, I know where the keys are and how English grammar works, but still everything about my writing process, especially in revision, is about taking the load off of my working memory so that space can be open to discovering ideas and pretty phrasings.

So.

My favorite and probably only life-changing revision strategy is reverse-outlining. I'm not much of an outliner for drafting—I may know where I'm going but the connections and particular path make themselves known as I go, so whatever my thinking brain might plan is rarely where my writing brain wants to wander—but once I have a draft, especially a messy one, or an unwieldy one, such that I can't see it all at once (literally or not), reverse-outlining is the key to handling it. It's basically a descriptive outline: You take the draft you have and make an outline of what's there. It can go paragraph-by-paragraph, section-by-section, or gesture-by-gesture, however makes sense to you. And then you have, usually on a single page, a map of what you have. You can see its shape and its roughness, you can see if you're repeating yourself (ah, paragraphs 12 and 23 do exactly the same thing!) or, at the very least, you can see the things you have and start thinking about how you might want to move them around.

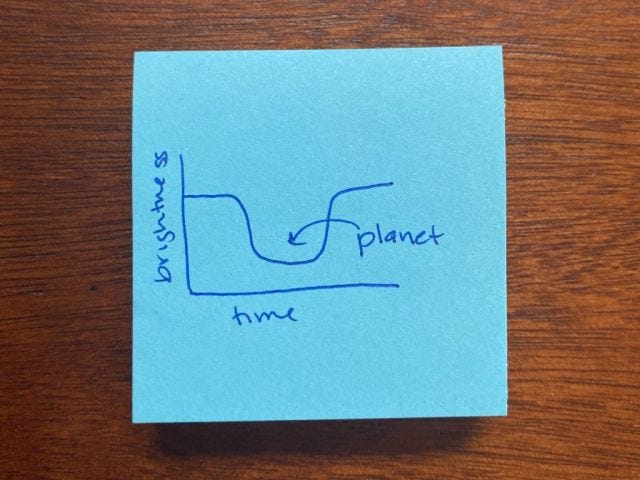

That was what I did earlier this week—reverse outlined each chapter on a page of my notebook, which revealed that chapter 2, on planets, was an utter wreck. (I'd never actually, it seems, turned the sections of early writing into anything even attempting cohesion.) So I took a bunch of post-it notes and wrote on each the elements I knew went into this chapter. Then I moved them around on my desk, putting together the puzzle—I'd find a pair or trio that I knew fit together, and then at least I had a bigger unit to play with, fewer distinct pieces to shuffle around. And so I've been spending this week making a new chapter that follows that post-it note outline, copy-pasting from the first draft when I can, writing new material when I need it. (That's what I need to do 5,000 words of after I finish writing this newsletter.) The post-its are color-coded (blue for theme, pink for science, orange for sci-fi, green for concepts) and it's reassuring to look at them as I work. Someone in the past figured this out for me!

The other thing that's been proving extremely helpful isn't writing-specific at all, but is also about taking pressure off your working memory (and satisfying color-coding): it's Airtable. I'm not sure what Airtable is meant to be, but for me it's a very flexible and full-of-features spreadsheet program. I learned about it from romance author Cat Sebastian, who long ago (2019!) tweeted about her revision strategy. I'd somehow remembered it and when my time came, I hunted it down.

The gist is, and this applies far beyond revision and writing!, make a list of everything, organize it, and then worry about one item at a time. Working memory! Cat's thread introduced me to Airtable, which has just enough more features than google docs to be extremely useful but not overwhelming. I've been using it to capture and hold everything I'd like to do in revision, which is so many items too many that one of my columns is "priority / definitely / probably / maybe / if time," the latter categories holding all sorts of further research plans and ideas that will never be gotten to, but are reassuringly not forgotten or lost. Every task has a row, and it's labeled with the chapter and the sort of work (research, new writing, revision, etc.), check boxes for if it's in progress or done (which Airtable conveniently can sort by), whether it needs university library access (recently lost; a whole thing), and "comb," which is a revision strategy I learned from my friend Maddox when we were both teaching comp, which is about organizing revision from biggest/most global to tiny surfacey fixes—getting the big tangles out first.

By this point you probably know if Airtable or something like it is right for you: Did that list of color-coded columns sound appealing or make you want to run away? But know that I don't use this intense organization because I'm naturally organized, I use it exactly because I'm not, because I forget things and my brain skips around to new ideas and then as I'm falling asleep I remember something I'd forgotten and then, boom, I'm wide awake and the baby will be up in six hours. The way Airtable sorts means that this week, working on the Planets chapter, I was able to be looking only at that chapter's tasks, but I knew that everything else was still safe, ready for me to come back to it hopefully Monday, I really have so little time.

Other things that are proving helpful: trail mix, ice packs, my little timer clock that measures out 25-minute work sessions and 5-minute breaks that are really more like 10 and that's okay. I recently discovered that the hyacinth bulbs we planted around what will hopefully be a trio of giant alliums are grape hyacinths, aka tiny little guys topping out at maybe six inches tall. It's absurd, but if you squat way down to the ground they smell amazing.

Thank you for reading! Please pardon any typos or sentences that fade out half-way, they're what let me send this out free and weekly. If you enjoyed this newsletter and want to share it, or were forwarded this edition and want to subscribe, the link is tinyletter.com/jaimealyse. You can also follow me on twitter here, and when my book is done and ready to be preordered this is where I will tell you about that.